Rudolfinum

May 27 at 8

|

| Boldly going where no violinist has gone before. |

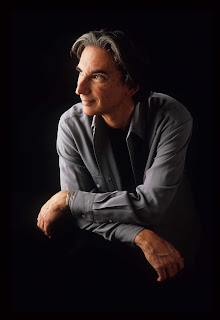

American violinist Robert McDuffie is nothing if not audacious.

When he was looking for a companion piece to The Four Seasons in 2000, he decided that American composer Philip Glass would be a perfect choice to write a contemporary version of Vivaldi’s Baroque classic. So he contacted Glass, who he barely knew, to pitch the project, telling him, “You’re the American Vivaldi.”

“Luckily, he bit,” McDuffie said in a phone interview last week from Poznan, Poland. “I don’t know if he liked that I called him the American Vivaldi, or agreed with that. But he loved the idea, and cheerfully agreed to take on the project.”

It was another seven years before Glass could find the time to actually compose what became his second violin concerto, The American Seasons. McDuffie premiered it in tandem with The Four Seasons in Toronto in 2009, and has been on the road with the program ever since. He will play it at the Rudolfinum Friday night.

“The premiere was in December, and by that time the following year, I had given about 40 performances of it,” McDuffie said. “It really turned out to be a big hit. Glass has his own following, which has helped – I can’t believe the number of pierced body parts I’ve seen in some places. But I find that traditional concertgoers also love the music.”

There are some connections between the pieces. Glass borrowed a few motifs as reference points, and as McDuffie noted, “Both of the composers use repeated bass notes, and both pieces have very seductive melodies up top.” But in almost every other respect, The American Seasons is a distinctly modern work.

“I wanted it to be serious, but in a showbizzy way, with a catchy theme that would attract presenters,” McDuffie explained. “In that sense, it was a business decision. I wanted something thoughtful, but accessible. I also asked Glass to give me a – I don’t know what else to call it – a kick-ass, rock ’n’ roll ending. And he completely agreed with that.”

There were discussions on other points, like whether to base the music on text, as Vivaldi did with the original. The poetry of Alan Ginsberg was considered before the text idea was scrapped. McDuffie and Glass also talked about making the new work a multimedia piece, adding another dimension with, say, a lighting artist.

“We went back and forth on that a lot,” McDuffie said. “Finally we decided that he would just write a piece that would stand on its own. It uses the same orchestration as Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, except with a synthesizer replacing the harpsichord, to give it his trademark sound.

“The only thing we couldn’t agree on what was to title the movements. His summer was my winter. So we finally decided, no titles – we’ll let the audience decide what season each movement is. Which is great, it brings the audience into the piece.”

While pairing a Baroque and modern work might be a clever marketing ploy, it presents a challenge for a serious musician. McDuffie is well-versed in the 20th-century American repertoire – he’s been lauded for his performances and recordings of Barber, Bernstein and Adams. But playing Baroque music properly is an entirely different discipline, and McDuffie admitted that he was lucky to have good teachers.

“When I first started touring this program, I was very fortunate to be with one of the best Baroque orchestras in the world, the Venice Baroque Orchestra,” he said. “It was an amazing growing experience for me. I was playing Vivaldi, I guess you would say with an American approach, whatever that is. They of course have their own approach – it’s in their DNA. And it’s very energetic and vigorous. So I was able to lock into that, and benefit from their experience.”

In Prague, McDuffie will be backed by the Prague Philharmonia, a young orchestra with the flexibility and range to accommodate both Baroque and modern music. This will not be his first experience with a Czech ensemble. That occurred in 1982, when he was 23 years old and the Czech Philharmonic was touring the United States under the baton of the legendary Václav Neumann.

“They were in Ames, Iowa, and needed someone to play Dvořák’s violin concerto,” McDuffie recalled. “I had never played it. But my manager lied, and said I had played it dozens of times. The night before the concert, I was still learning and memorizing the piece. I remember asking God, why am I a violinist? I felt like I was walking on a high wire without a net.

“I don’t remember much about the performance, it’s a blur now. I didn’t embarrass myself. Still, it was a huge risk.”

Fortunately, Prague Spring organizers have taken the risk out of this appearance.

“They asked me to switch the order,” McDuffie confided. “Usually I play Vivaldi first, and Glass second. In Prague, I’ll play Glass first, then Vivaldi. It’s okay with me, I trust the Prague Spring people. I’m sure they know they know their audience.”

Indeed they do.

For more on Robert McDuffie: http://www.robertmcduffie.com/